Research

Back in the early 1990s, I became interested in the history of Japan's friendship with the United States through baseball. Team tours began as early as 1905, with Waseda University's visit to the U.S. Besides the international tours, another interesting aspect is the experience of American players in Japan, and more recently that of Japanese players in the U.S. I noticed that a list of foreign players in Japan (mostly American) had been created from 1950 (beginning of Japan's two-league system) to present. Since professional baseball in Japan began in 1936, I began creating a list of foreign players from 1936-49. With assistance from Jeff Alcorn and Yoichi Nagata, I came up with a fairly complete list to distribute within a small community of Japanese baseball enthusiasts.

One player that immediately caught my attention was a fellow named Jimmy Bonna (this was the Japaenese translation). From Japanese news articles, we learned that Jimmy was an African American player who was signed to play in Japan in late 1936. I tried to locate American articles on him in those early Internet days, but without success. In 2010, my friend Jeff Kusumoto in Japan located a fascinating chapter on Jimmy's time in Japan written in the 1950s by a Japanese author. A short while later, it was discovered that Jimmy's actual name was James Everett Bonner. With an Ancestry.com account I was able to make some good progress on Jimmy's biography. Eventually, Bill Staples Jr. asked me to write a biography on Jimmy for his book Gentle Black Giants (Sayama & Staples, Jr.). With the material I had gathered along with Bill's access to Newspapers.com, I was able to produce a fairly decent overview of Jimmy's life, with a focus on his stint in Japan.

From Louisiana to California

James Everett Bonner was born on September 18, 1906 in Mansfield, Louisiana, a predominantly African American lumber town. Jimmy played baseball in junior high, and by 1932 he was a utility player for the Shreveport Black Sports baseball team while employed as a tailor. Standing 5 feet, 10 inches, Jimmy threw right and batted left. Later that year, twenty-six-year-old Jimmy decided to move out to West Oakland, a neighborhood in Oakland, California with his wife Lillian. During the Depression, California was seen by many as a land of opportunity. Oakland was the last stop west along the first transcontinental railroad. By 1900, African Americans working as Pullman porters helped establish an ethnically diverse, middle class community in West Oakland.

In 1934, Jimmy played for the San Francisco Giants (also referred to as the San Francisco Colored Giants). This was an independent, semi-pro African American team that mostly played against Caucasian teams within the San Francisco Bay Area. In 1935, Bonner joined the Oakland Black Sox. In one game against Emeryville, he started in right field. When the pitcher got in trouble in the fifth inning, Jimmy was called in to replace him. Jimmy allowed only two bases on balls, and struck out six. In 1936, Jimmy pitched for the Berkeley Grays of the Berkeley International League. This league was an ethnic mix of Bay Area teams. Their home field was San Pablo Park, where games could draw crowds of up to 2,000.

In a game on April 19, 1936, Jimmy whiffed seventeen batters in a contest against the Berkeley Cardinals. This broke the previous league record of fourteen strikeouts. Then on May 18, Jimmy shut out the strong Athens Elks. He allowed only two singles to win 9-0. Jimmy was referred to as "Satchel" Jim by both the Oakland Tribune and the Berkeley Gazette. He also led the team at the plate, hitting two for four at bats and driving in a run.

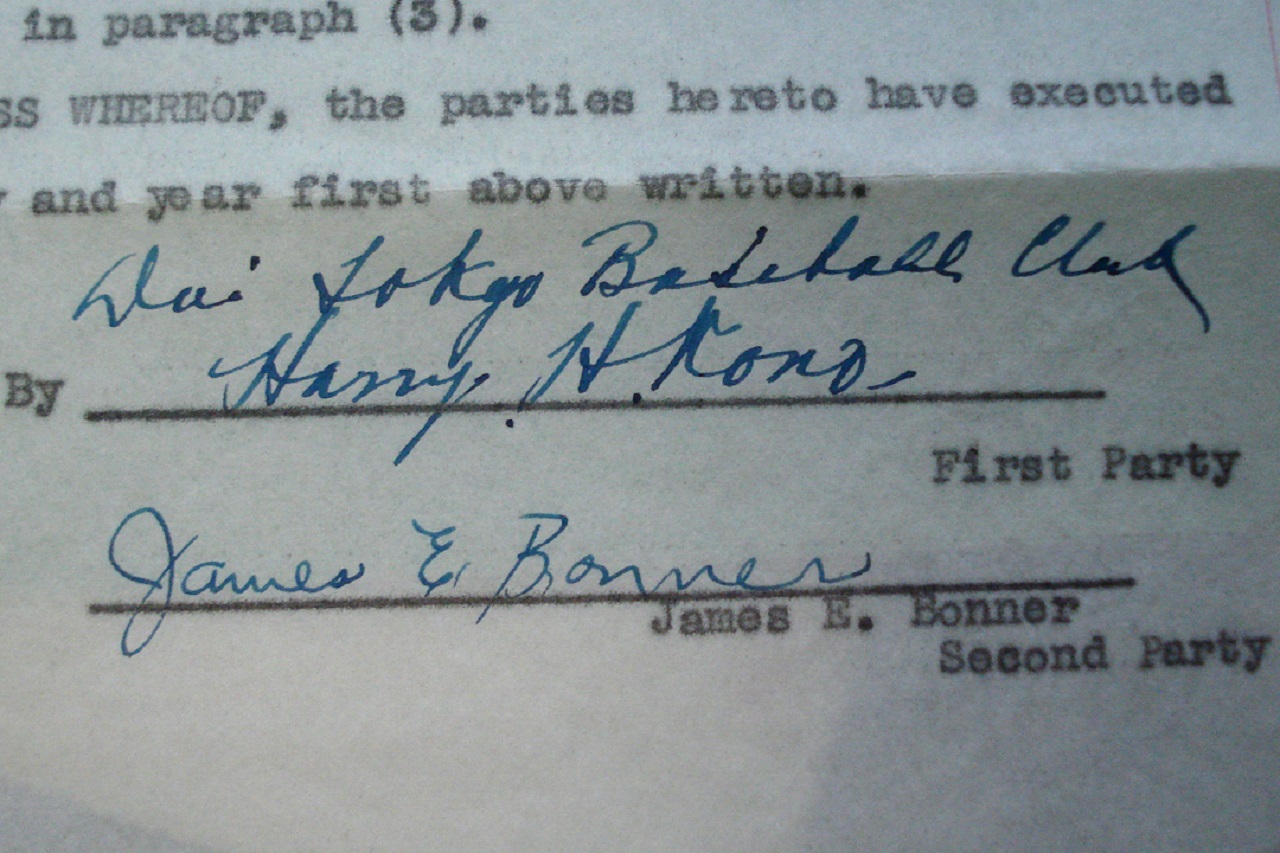

On September 5 and 6, Jimmy led the Civilian Conservation Corp's San Pablo Dam team to the CCC championship. He accomplished this by pitching three complete games in two days to take the series 3-1. Jimmy's success had caught the attention of Harry H. Kono, a successful Japanese American businessman based in Alameda. On September 8, Kono, working as an agent for the Dai Tokyo Baseball Club, signed Jimmy to play in the newly formed Japanese Professional Baseball League. Jimmy's team had been formed in February of that year and had been struggling. They were hoping that Jimmy's talent would lift them from the depths of the cellar.

From California to Japan

Jimmy arrived in Japan on October 5, 1936. In his meeting with the team management, Jimmy really talked himself up, saying that his fastball was so fast that you couldn't see it! He concluded by stating that, "I'd like to win everything, and set a new strikeout record." He negotiated a fine salary that even included steak for breakfast each morning!

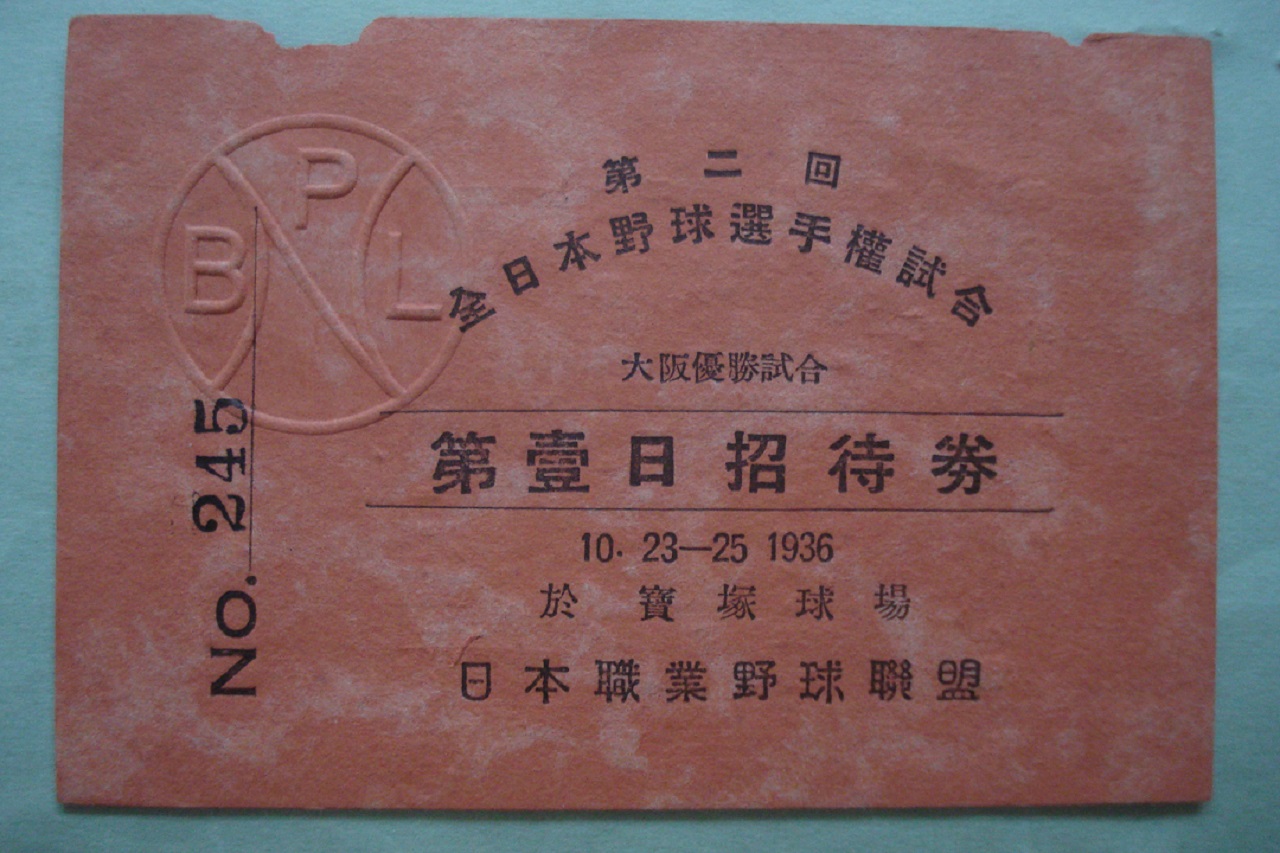

Jimmy's first pitching assignment was October 23, during the Osaka Tournament, the third of six tournaments that made up the fall season. It was Dai Tokyo's first game of the tournament, and they were scheduled to play against the strong Osaka Tigers. Before the game, the Tiger's Hawaiian pitcher and future Hall of Famer Tadashi Henry "Bozo" Wakabayashi had an opportunity to speak with Jimmy. Jimmy told Bozo that he could shut out the Tigers! Bozo replied, "Oh, that's interesting. Please do it! I'll see you at the plate."

Unfortunately, for whatever reasons, Jimmy pitched poorly, suffering from control issues. He gave up walks, not only in his first game, but in every game he pitched. Jimmy did have some success as a batter and fielder, though even his fielding needed some improvement. Ultimately, Dai Tokyo was disappointed that they hadn't found the pitcher that they were seeking, and decided to let Jimmy go after November 10 (his final game). Japanese records show that Jimmy played in seven official games. He pitched in four of those games and finished with a win-loss record of 0-1 and an era of 9.90 in 9 and 2/3 innings pitched. Against fifty-two batters, he walked fourteen and only struck out two. At the plate, he finished with eleven hits in twenty-four at bats for a .458 batting average.

And so we're left wondering what accounted for Jimmy's poor showing in Japan. One possible explanation is the quality of the Japanese batters. Though professional baseball was new in Japan, baseball had been popular in Japan since the 1870s. High school and University players trained hard in the basics like patience at the plate. In 1936, the average height of a Japanese male was 5 feet, 4 inches. This would likely result in a smaller strike zone than Jimmy was used to. Another factor could have been the ball itself. The Japanese baseball was slightly smaller than an American ball. Japanese American player Jiggs Yamada, who toured Japan in 1925, complained that the leather of the Japanese ball was slick. For a developing pitcher still working on control, these factors might have made a difference in his performance.

Return to Oakland

After returning home to Lillian in Oakland in December 1936, Jimmy began his career as a Pullman porter. He continued playing baseball as his schedule allowed, pitching well for the Berkeley Grays and the California Yellow Jackets in 1937. He played for the California Colored Giants in 1938 through at least 1940. Jimmy enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1943, and then returned to the Pullman Company after the war where he remained as a porter until his death at fifty-two on May 10, 1963. Jimmy had no children, but was survived by his wife Lillian who passed away in 1984. Jimmy was buried in Mansfield, Louisiana and the old house is no longer there. I was fortunate though to make contact with Jimmy's great-niece Lisa, and have enjoyed sharing his fascinating story with her and her family.

Further Reading from the California Room:

- Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan by Kazuo Sayama and Bill Staples, Jr.

- Pullman Porters and West Oakland by Thomas Tramble

- The Golden Game: the Story of California Baseball by Kevin Nelson

- California Room Index: baseball

Add a comment to: Looking Back: The First Black Player in Japanese Baseball